Anything above 5% is a social inequity

Via Commonwealth Magazine.

By Dr. Katherine Gergen Barnett

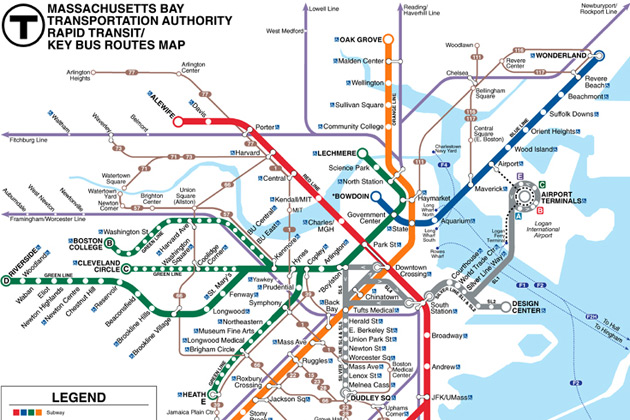

AS THE BITTER COLD has returned to the streets of Boston, I have been driven into the warmth of the T more than once on my bike commute home from the hospital. The scene there is familiar – workers weary at the end of the day, parents with children swaddled in snow pants, young adults making their way. The English language is wrapped into many other languages, many of which I now recognize from my 11 years working at Boston Medical Center, New England’s largest safety net hospital.

The MBTA, though rife with many concerns about functionality over the past year, has long served as a window into the population of Boston. As such, it is a great equalizer. According to estimates, the typical weekday ridership of the T is 1.3 million. On weekends and holidays it is around 500,000. These numbers make the Boston T the fifth-busiest transit agency in the nation. My patients are among these riders, using the rail lines carved through the city as their way of getting to one of many jobs, numerous appointments, and children’s schools.

This means of commuting may soon become financially untenable to some of Boston’s T riders. On January 4 this year, the governor’s Fiscal and Management Control Board released two possible scenarios for fare increases to go into effect in July 2016. One raises fares by nearly 7 percent; the other is more radical, increasing fares by 10 percent. This will not be the first time the MBTA has increased its fares recently. In fact, since 2000 the MBTA has increased fares five times: in 2000, 2004, 2007, 2012 and 2014. Fares have increased 6.1 percent per year on average between 2000 and 2014, which is significantly more than inflation.

The proposal for fare increases comes from a seemingly justifiable position: the MBTA is looking to address an estimated $242 million deficit in the next year. However, critics of the fare hikes, such as the Conservation Law Foundation, have correctly pointed out that a system-wide average fare increase of over 5 percent is not needed to balance the MBTA’s FY2017 operating budget. This deficit has already been closed with additional state assistance (held constant from last year at $187 million) coupled with cost reductions identified by the MBTA (such as the elimination of non-essential spending increases and reductions in unnecessary materials, services, and supplies), which will add at least another $55 million.

As a resident of Boston, I deeply want the T to become solvent and a dependable source of timely transport. However, as a physician who cares for individuals whose incomes are often 200 percent below the poverty line, I am extremely concerned what this hike in fares will do to the lives and well-being of many residents of Boston. Just recently, a patient of mine – a young woman who is already a mother of four and a grandmother – was late to her appointment. Knowing her medical and psychological issues were complex and urgent, I folded her into my schedule and she began the visit crying, stating that one of the reasons she was late is that she could not find the fare to travel across the city. The proposed increases may mean that she will become one of many who no longer are able to easily access needed appointments, subjecting her to potential poorer health outcomes and increased social isolation.

I am thus joining others in imploring the governor to look for different means than a passenger fare increase of up to 10 percent to bridge any gap in the MBTA’s funding. Asking for a greater than 5 percent fare hike every other year (a predictable and modest increase that people can budget for) from riders is a social inequity. What is more, we need to start thinking about transportation more holistically: the well-being of our T system can be fed, in part, by revenue sources such as higher taxes on individual drivers. State and federal gas taxes are at an all-time low and our bridge and tunnel tolls are the lowest compared to other large metropolitan areas. Bringing our T system back to health by means outside of radical fare hikes also means that, as a city, we can recommit to bringing people to appointments, schools, and groceries safely and with a sense of true equity.

Dr. Katherine Gergen Barnett is the vice chair of primary care innovation and transformation at the Boston University Medical Center’s Department of Family Medicine.